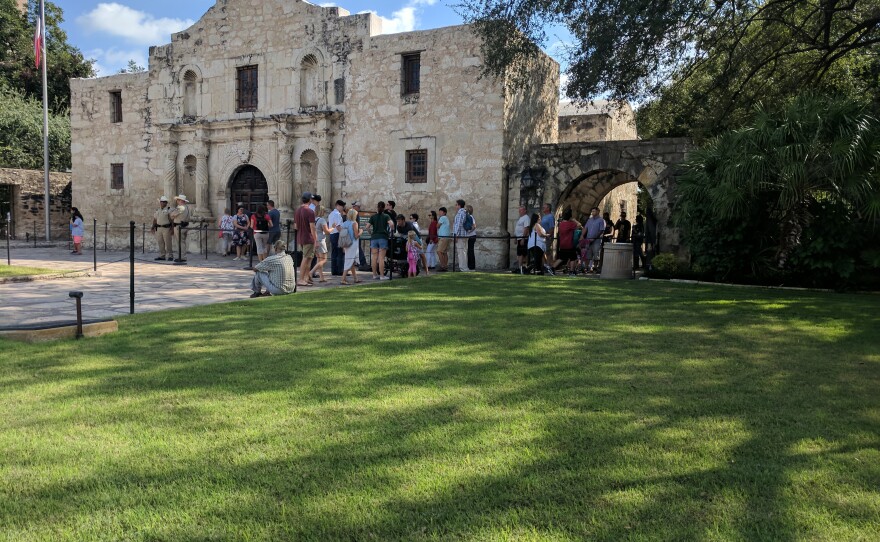

A line of tourists stretches twenty yards from the Alamo chapel doors. Two and a half million people visit the four-acre lot every year, the site of the famous 1836 siege by surrounding Mexican forces that would go on to inspire countless books and films.

"You know, honestly, I expected it to be a bit bigger,” says Abilene's Vanessa Russel who just snapped a photo of herself in front of the chapel.

More than 180 years later, the Alamo is surrounded again, now by the seventh largest metropolitan area in the country. Encroached and limited, the remaining grounds often leave tourists like Russel wondering how such a grand history played out in such a small space.

Russel says Alamo Defender Andrew Kent was one of her ancestors, "and I’ve grown up hearing the stories of the Alamo so, yeah--I thought it would be quite a bit bigger.”

The company Alamo Reality wants to solve that problem by taking advantage of people’s phones and tablets to bring them back in time.

“To show people what the Alamo looked like in 1836, where right now most people that get there think the Alamo church is where the whole battle took place, and they think 'g’all, that’s awful small,' ” says company co-founder Michael McGar.

By recreating the structure digitally in augmented reality -- or the ability to superimpose computer-generated content on the real world -- anyone can hold up their device and see walls and rooms long gone, characters of the Alamo siege and scenes from its history. McGar believes people will connect in a way they couldn’t in the average 10-minute trip.

Imagine standing in front of characters you had only read about in textbooks, says Alamo Reality’s Chipp Walters. "We can have Davy Crockett – at a very high resolution -- standing in front of you, loading his musket with a voiceover talking about what kind of challenges he faced.”

But the app won't just focus on the defenders of the Alamo and its siege, says McGar. The geo-located content will have multiple scenes, some from the siege, some that predate it, some focusing solely on the tribes that populated the area before the Spanish arrived.

Next March, the company wants to roll out the free app alongside additional content and educational materials they can sell. Walters displays a flat, fabric mat of the Alamo compound about double the size of a placemat. It's made of fabric to cut down on glare, which can prevent phones from recognizing targets and launching content.

Walters has no problem. His iPad comes to life, displaying the Alamo walls and characters strolling the grounds. A narrator tells us about Davy Crockett, who we can see firing his gun into the distance. Walters zooms in on Crockett and turns his iPad as the scene shifts to reveal more of a fully built 360 degree scene.

This "Reality Board" along with playing cards -- that through your phone take on three dimensions and interact with one another when placed side by side -- are just a couple of the products they want to build out.

Augmented Reality in historic sites like the Alamo is largely uncharted territory, says Barry Joseph, associate director for digital learning at the American Museum of Natural History.

“I think its an infrastructure question," Joseph says. "I could be wrong about this. Those locations tend to be smaller and less likely to develop technology enhancing visitor experience."

Not so in museums, where they are gaining a foothold. The Center for Future of Museums highlighted Augmented Reality in last's year's TrendsWatch report.

In the last 18 months, Joseph has helped launch the Natural History Museum’s efforts, which range from allowing people to shrink down to explore the forest floor to staff experimenting with loading CT scans of animals museum scientists are examining on site.

“So, in other words, visitors would experience holding a shark skull in their hand or a bat skull,” says Joseph.

Hundreds of thousands have used their AR apps, and Joseph says it has shown the museum that their patrons want to use their own devices to tear down the barriers between exhibits and give behind the scenes views on what their scientists are working on.

Alamo Reality wants to tear down those same barriers for history. With a team of historians they are creating scenes for people to watch on the spot they actually happened. Like the death of Jim Bowie at a currently unmarked location.

Michael McGar says it turns people’s intellectual responses into emotional ones. “I can’t just look at it, and say that’s a place where somebody died. You saw them die. That makes a huge difference.”

And the Alamo is just the beginning, they say. McGar can see this same technology being used at other historic sites like Gettysburg, connecting people beyond words with the past.