The San Antonio Independent School District launched a bold new enrollment policy at five specialty schools this year, weighing the lottery based on income and geography to maintain a balance of working class and middle class students.

Creating socially and economically diverse schools goes against the status quo in a city as economically segregated as San Antonio. The question now is whether families will like the idea enough to return in years to come.

Most of the city’s neighborhoods — and most schools — are divided by class. And it didn’t get that way by chance.

Throughout the 20th century, racially restricted housing development kept black and Hispanic families out of San Antonio’s middle class neighborhoods, even when they could afford it. The predominantly white city leaders continued to drive development to the north, away from low-income neighborhoods. It was not until 1977 that the City Council converted to single-member districts, giving the south, east, and west sides of town equal representation in city government.

While racial restriction is no longer legal, the economic geography of the city is still highly uneven, according to researcher Richard Florida.

When school districts were given the chance to consolidate in 1948, the decisions were largely economic, with no district willing to take on too much liability from consolidating with the poorest districts. The resulting 16 school districts in San Antonio are a legacy of 20th century inequities, according to Trinity University Professor Christine Drennon.

Steele Montessori in southeast San Antonio is one of the rare schools that is socioeconomically diverse. It opened this school year in an elementary school previously closed by the district.

The school is currently about half low-income and half middle-income students, and the district intends to keep it that way by carefully controlling enrollment as the school becomes more popular. It’s one of the five schools with weighted lotteries, alongside Cast Tech High School, Advanced Learning Academy, and the Mark Twain and Irving dual language academies.

Of the new applicants offered seats at Steele next year, 51 percent are low-income and 49 percent are not.

For the most part, families say they are happy with the school environment. But there have been some bumps in the road.

“He’s heard words here that we don’t use at home, and so it’s kind of like taken us aback. But we do know that there are different education levels from the parent perspective, and the way they run their households,” said Belinda De Luna, a public school teacher in a neighboring district.

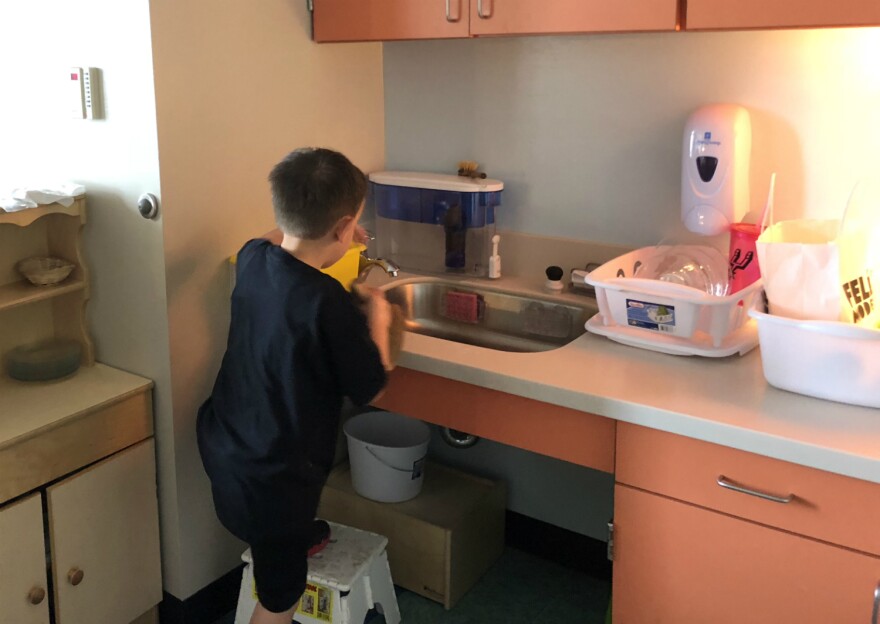

She said she was attracted by the Montessori model, and decided to send her son Luke to kindergarten at Steele after attending a private preschool.

Her husband Paul De Luna, who works at a bank, said they considered sending Luke to a Catholic school.

“We knew that within the Catholic school he was going to get a structure based on religious beliefs and religious content,” he said.

Principal Laura Christenberry is treating the school’s diversity as an opportunity to build social skills.

“When you bring students together of a variety of different backgrounds, and a variety of different parenting styles, incomes, where they grew up, how their parents grew up — how what you may think is okay may offend someone else, and vice-versa,” Christenberry said.

She said Steele has only had a few isolated discipline incidents this year, and they’ve been evenly spread across all socioeconomic groups.

“But what’s also important is for parents to also know that while we are a Montessori school we are not a private school,” she said. “This is a public school and we will take all students and that means we will address all of their needs.”

Mohammed Choudhury, the head of the district’s enrollment office, is trying to head off another potential roadblock by encouraging his schools to build a welcoming culture from the ground up.

“If you don’t actually design for guardrails for how families engage with one another you can have PTAs that are dominated with one type of family,” Choudhury said.

In 2016, researcher Alexandra Freidus analyzed communications among parent groups at mixed-income schools, and noted that wealthier parents tended to suggest and move forward with their priorities, while lower income parents were largely ignored.

To prevent this sort of dynamic from taking over at Steele, Christenberry strategically created opportunities for both working- and middle-class parents to volunteer at Steele Montessori.

“As we grow, I think that’s when it’s going to become more important to be very intentional,” Christenberry said.

Stay-at-home mom Graciela Chavarría said she can tell that some families are better off than others when she volunteers at the school.

“But they’re really nice,” Chavarría said. “I think they don’t discriminate whether you have money or not. So I like that.”

She and her husband Pedro Palacios said they have seen their 5-year-old son Jacob blossom at Steele after needing speech therapy in Head Start.

“He composes more full sentences now and he expresses what he’s feeling and he follows directions and I think this school is big on discipline and following a routine and rules,” said Palacios, a mechanic and construction worker.

While Palacios and Chavarría are happy about Jacob’s academic progress, there have been some social adjustments for the family. Last semester, Jacob was invited to a wealthier classmate’s birthday party.

“We’d never been (to) that kind of party,” Palacios said. “It’s a different type of setting, because they’re another step up in wealth.”

For generations, families in San Antonio have lived in neighborhoods and gone to schools with people like themselves. Many have never socialized with people from a different income bracket. And that can make things awkward, even when people have the best of intentions.

But Chavarría said it was a different story for Jacob and the kids at the birthday party.

“They were playing like nothing, they were having fun and everything,” she said.

SAISD’s Mohammed Choudhury said that’s the whole point of an economically integrated school: If you bring children together when they’re young, they learn and grow together.

“That is happening every day on the playground, in the hallways and when they are working in groups, and you just can’t buy that effect,” Choudhury said.

Research shows that students who develop these skills early become adults who can work in diverse environments, and surveys show that’s a characteristic employers prize.

In one of the first districts to propose socioeconomic integration — LaCrosse, Wisconsin the local business community was one of its strongest advocates, according to Richard Kahlenberg of the Century Foundation, a progressive think tank.

The district is counting on families recognizing how valuable that is. As they do, the district expects demand to increase. That, in turn, will increase the need to control enrollment and keep the schools economically diverse.

This story is part 2 of a series on San Antonio ISD’s plan to keep some of its schools economically diverse. Part 1 broke down how the plan works and why it matters.

Camille Phillips and Bekah McNeel can be reached on Twitter @cmpcamille and @BekahMcneel