For decades during the Cold War, the Army carried out chemical and biological testing experiments on more than 7,000 of its own soldiers at the Edgewood Arsenal in Maryland. The GIs — all volunteers — were sworn to secrecy and told they would experience no long-term health effects.

Some soldiers tested protective clothing, while others were exposed to nerve agents, mustard gas, and psychoactive drugs with no plan for follow-up care.

Most didn’t realize what they’d signed up for.

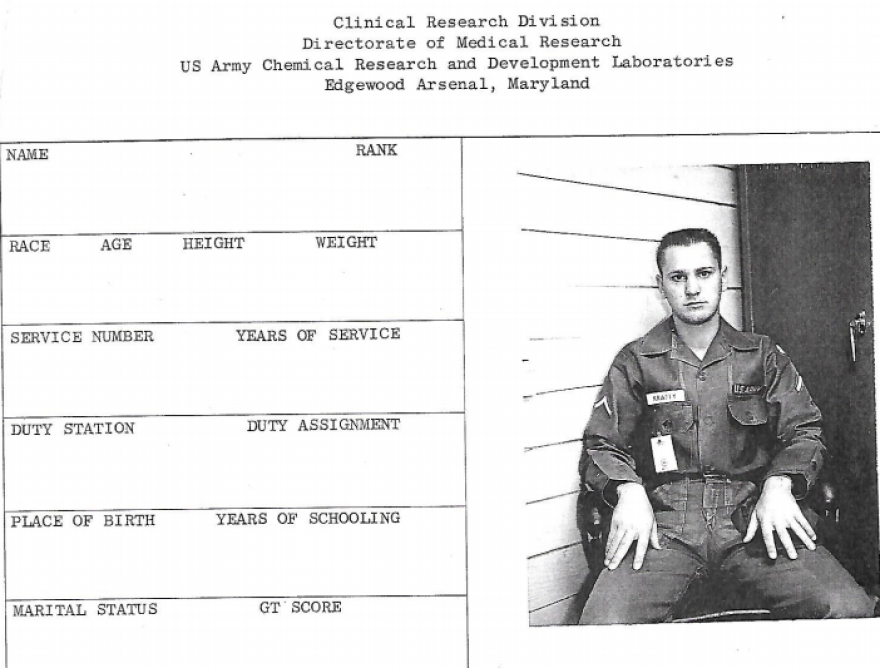

Bob Krafty was just out of his teens when — in 1965 — he was offered temporary duty at Edgewood. The offer was attractive: it would mean no kitchen duty, a private room and three days off per week. The Army told him he’d be helping to end the war in Vietnam.

“I was naive. I was patriotic,” Krafty said. “My government would never hurt me. You know, at first it's embarrassing to know you were sucked in.”

Once he arrived at Edgewood, Krafty heard talk of a new chemical warfare strategy, one that would minimize American casualties.

“I was told that, theoretically, we could take a chemical and dump it behind the enemy lines,” he said. “Then in 12 hours, 24 hours, go behind there and gather them up. This way, you're not being killed. You're not killing them.”

Krafty remembers the experiments vividly. The Army once put him in a padded room for three days and made him breathe an aerosol pesticide used by the military as a nerve agent.

“They put it over my nose and mouth,” he said. “I felt weak — dizzy. They tested us day and night — woke us up during the night taking blood pressure, asking what sensations we're feeling.”

Krafty left Edgewood after two months and remained stateside instead of going to Vietnam.

By the time he reached his mid-20s, his hands shook so badly he struggled to countersink a nail. He later developed other health problems, including prostate cancer and symptoms of post-traumatic stress.

It was only decades later that he found out through his own research that he had been exposed to dangerous chemicals. But when Krafty obtained his Army health records and applied for VA disability benefits, he was rejected. The VA said it lacked adequate evidence to show that Krafty’s health problems were connected to his time in service.

Ordered To Notify

In 2013, a federal court ruled that the Army had to notify veterans of possible long-term health effects from their time at Edgewood. That same court later required the Army to provide them with medical care as well.

“Notice is important; one, so vets can get proper medical treatment and understand the diagnosis for their particular health problems, but also because (of) benefits claims processes,” said Ben Patterson of Morrison and Foerster, the law firm representing the Edgewood test veterans. “For example with the VA, they need that additional support in order to get their claims granted.”

Starting in November, the Army mailed about 4,000 letters to test vets around the country. They included applications for medical care, but made no direct mention of Edgewood Arsenal. They also didn’t provide any information about the specific chemicals vets were exposed to.

“It’s so generic. It’s obvious that they didn’t even know what they were doing,” said Frank Rochelle, who is one of the original plaintiffs in the case, which began in 2009. “The forms they want you to fill out are basically just delaying the whole system.

“They’re hoping that we’ll die.”

Some veterans — like Krafty — never received a letter. Others that did, like Rochelle, face an uphill battle to qualify for care and get their health information.

“I don't think these guys are acting in good faith,” Krafty said. “I didn't receive any notification or application from them. But I know they have my files — they sent them to me three times.”

But the Army said notifying vets isn’t as easy as it sounds.

Bill Fitzhugh, who is the program director of the medical care injunction for participants of chemical or biological substance testing programs at the Army Public Health Center, said the Army first has to validate where veterans are before releasing any private health information.

“So they've got to get their DD214 (discharge paperwork) and figure out where it is,” Fitzhugh said. “Then they have to show proof of participation, so that might be in some other different place. The last piece is to get the application form signed by their physician.”

The Army said some veterans didn’t receive letters because parts of their names, social security numbers, or serial numbers were missing from its database.

Some of the records from Edgewood have been destroyed – or are difficult to make sense of.

“The major issues that we’re talking about is our data is incomplete. The data that we’re dealing with sometimes is handwritten notes, notebooks,” Fitzhugh said. “It’s definitely not automated.”

Bureaucratic Obstacles

As of Feb. 1, the Army had only received 64 medical care applications from veterans — 41, of which, were complete. There are an estimated 1,000 living test veterans from Edgewood.

According to a statement from Army Public Health: “We have sent over 265 letters to Veteran/Military Service Organizations requesting that they share the information with their members. We have reached out to the VA and they have placed the link to our website and a brief description of this program on their websites.”

"Let's face it. With the age, how many are dying off? How many don't know about it? In another 30 years, we're all gonna be gone."

Fitzhugh said it will be a while before the Army’s outreach gains traction.

“I was surprised to see how many responses we got as quickly as we did,” Fitzhugh said. “But we're expecting to see the number increase over time. And that's just for the known veterans — the ones that we sent out notification letters to. So that's one of the big things we're working on right now: How do we reach out to all of these veterans?”

That’s a question Bob Krafty spends a lot of time thinking about. He managed to get a copy of the Army’s medical care application on his own. But he says his fellow aging veterans can’t wait any longer.

“Let's face it. With the age, how many are dying off? How many don't know about it? In another 30 years, we're all gonna be gone,” he said. “Then Edgewood Arsenal is kind of going to go away.”

Eligible veterans can call the Army's hotline at 1-800-984-8523 for more information.

This story was produced by the American Homefront Project, a public media collaboration that reports on American military life and veterans. Funding comes from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting and the Bob Woodruff Foundation.

Carson Frame can be reached at carson@tpr.org or on Twitter @carson_frame